Research

Behavior

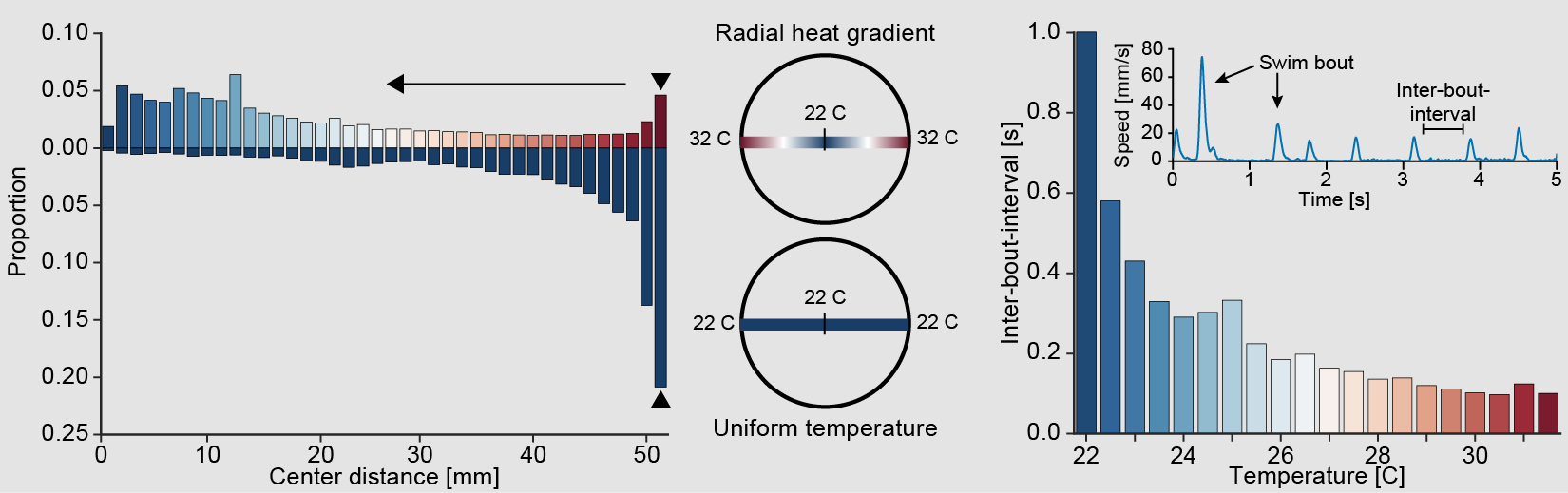

Left: Larval zebrafish heat avoidance in a gradient. Right: Modulation of inter-bout-interval by temperature.

In a heat gradient larval zebrafish will avoid areas of hot temperature and seek out cooler regions. Staying within water of the right temperature is likely critical for survival, especially since zebrafish can’t regulate their body temperature. To accomplish this task larval zebrafish need to sense temperature and modulate their behavior in a way that drives them away from heat.

Behavior is indeed modulated by temperature and one of the most striking changes is a decrease in rest intervals between swims (inter-bout-intervals). This leads to increased activity in warmer regions driving fish into cooler waters. We have recently used white noise temperature stimulation together with behavioral modeling in freely swimming larval zebrafish to understand over which timescales they integrate temperature information to make a behavioral decision (Haesemeyer et al., Cell Systems, 2015). This model revealed that larval zebrafish integrate temperature information for 500 ms before a bout and that both absolute temperature and changes in heat influence behavioral decisions. Importantly the behavioral model could accurately predict swimming in response to novel heat stimuli suggesting that it captures the transformation from heat sensation to behavior generation.

Functional imaging

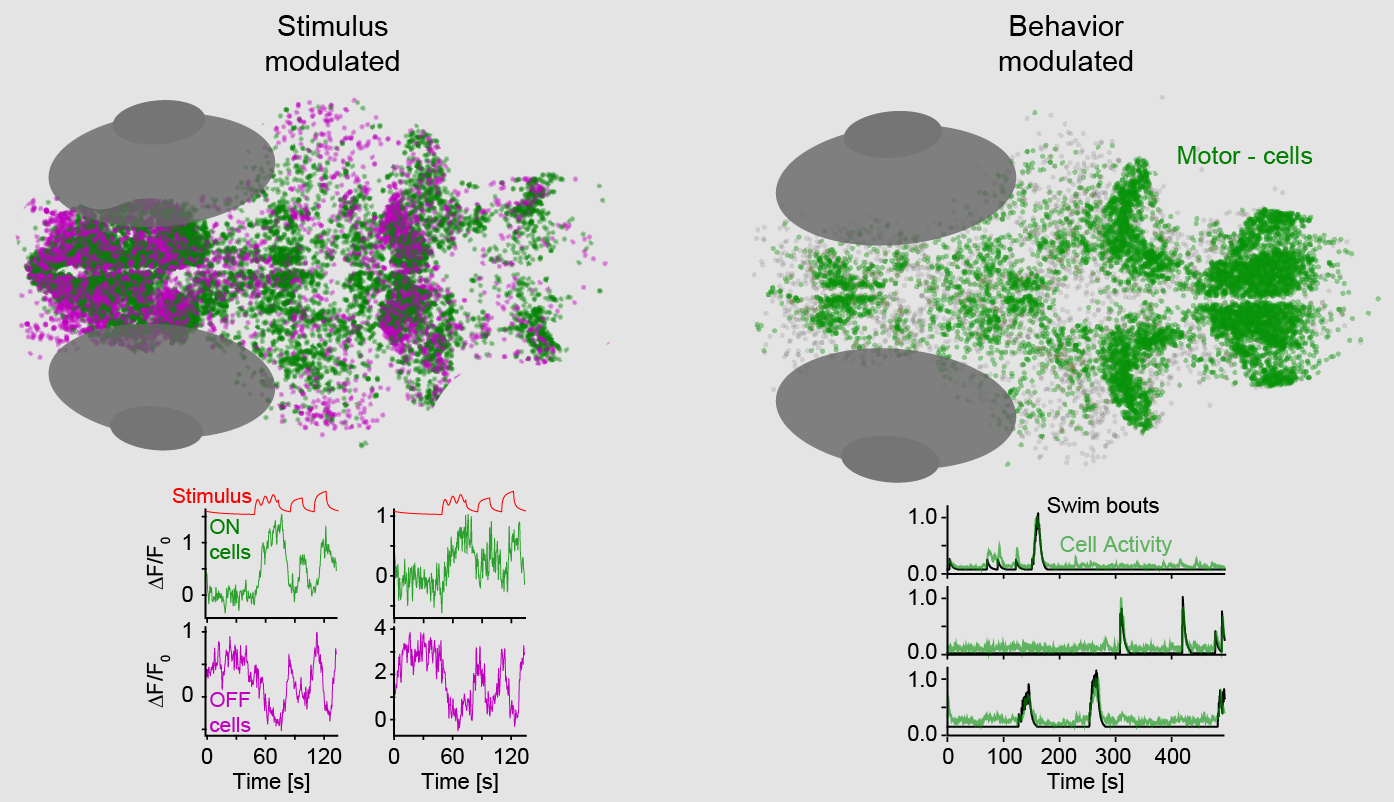

Identification of temperature (left) and behavior (right) modulated cells throughout the larval zebrafish brain.

We established brain wide 2-photon calcium imaging to record neuronal activity during heat stimulation while simultaneously recording behavioral output. This approach made it possible to identify neurons throughout the brain that are specifically related to temperature changes as well as behavioral elements. Temperature sensing cells were identified in the trigeminal ganglia, a pair of sensory ganglia of the trigeminal nerve that are thought to be responsible for encoding a variety of somatosensory modalities in all vertebrate animals. In the zebrafish two types of heat sensitive cells were identified in these ganglia: “ON cells” that were excited by increases in temperature and “OFF cells” that were inhibited upon temperature rise. Both cell types tracked the stimulus with slow dynamics and thus essentially represented the current temperature. Behavior related cells on the other hand were mostly confined to the anterior hindbrain and the cerebellum. Here we could identify cells encoding all observed behaviors as well as cells that were specific to swim type or laterality. We furthermore found a segregation of cells encoding spontaneous versus stimulus evoked behaviors hinting at a separation of behavioral states contingent on the stimulus. (Haesemeyer et al., Neuron, 2018)

Modeling

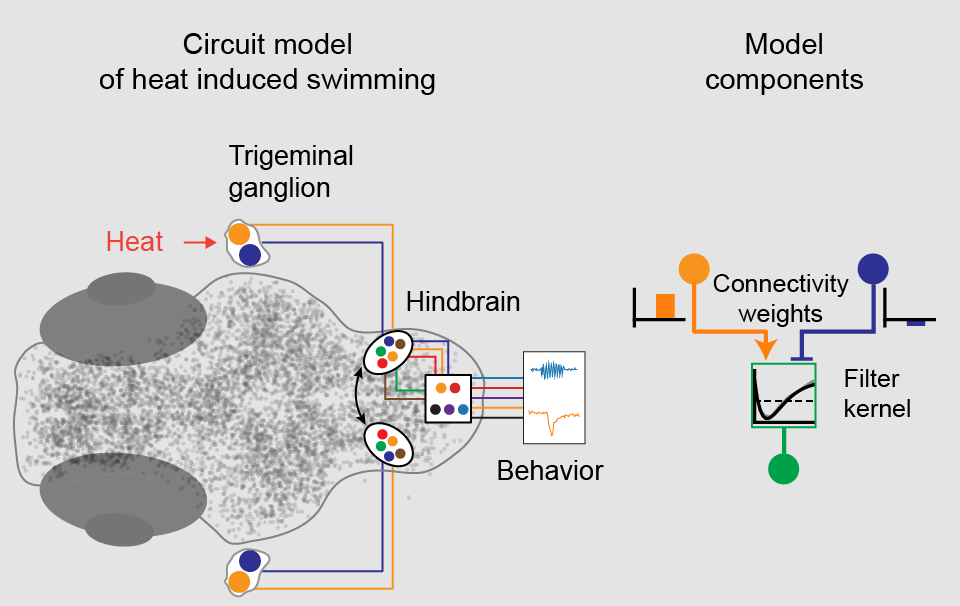

Structure (left) and components (right) of the dynamic model of heat induced swimming behavior.

Our brain wide imaging approach during heat induced swimming behavior revealed a critical step in the sensori-motor transformation from stimulus detection to behavior generation. Namely, while the sensory trigeminal ganglia represent the heat stimulus with one ON and one OFF type tracking the heat stimulus with slow dynamics, this representation greatly diversifies in a hindbrain area receiving trigeminal projections. Here, five types of temperature responsive cells were identified, including two cell types that were most sensitive to an increase in heat or a decrease in temperature. Thus, cells and circuits in the hindbrain are computing a derivative of the temperature stimulus that informs the larval zebrafish about the direction and magnitude of temperature change (warmer or colder). Importantly, these new cell types contained information that was required to explain larval zebrafish behavior with a simple linear model. This finding argues that larval zebrafish compute and use such information about temperature change in line with the previous behavioral study (Haesemeyer et al., Cell Systems, 2015).

We next developed a dynamic circuit model for heat perception in larval zebrafish that includes connectivity between cell types as well as how cells temporally transform their inputs. The strength of such models in neuroscience is that they allow researchers to form strong, testable predictions about circuit architecture. In particular we identified a hindbrain region that implements a small computational motif that calculates a derivative of its input to generate behavior and modeling predicts that this is achieved by a combination of adapting and non-adapting neurons in this region. Further studies guided by this model, including electrophysiology and connectomics, can reveal the full circuit implementation of this computational motif. Since the computation of the direction of change of a sensory stimulus allows for a simple form of prediction – if I know how something changes I know its value in the near future – it can be expected that this brain circuit motif is widespread throughout the animal kingdom. (Haesemeyer et al., Neuron, 2018)